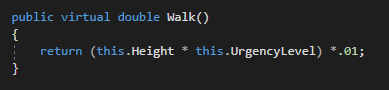

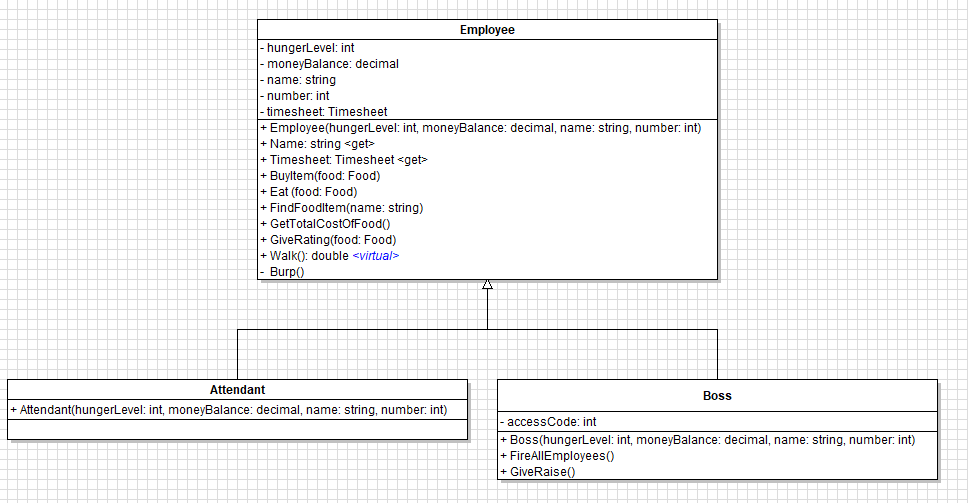

The accessors virtual and override work together. When we declare a method as virtual we are saying that the functionality of this method is okay and can be used, but if you want to do something other than this you can.

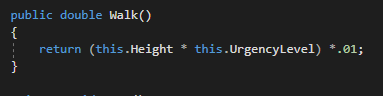

For example, let's define a method named Walk that returns 10% the Height of the Employee multiplied by their UrgencyLevel.

At this point every single class that descends from Employee has to use this method if they want to Walk, which represents the average walk speed. This is somewhat of an issue, though, because the Boss says that Attendants should be faster when they walk because they have more to do. We can't change the Walk method just because of that, though, because then our lazy boss would have to walk way faster than they want to. To make this work, then, we will make the Walk method virtual.

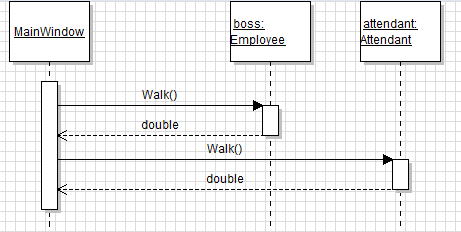

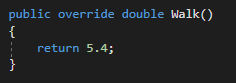

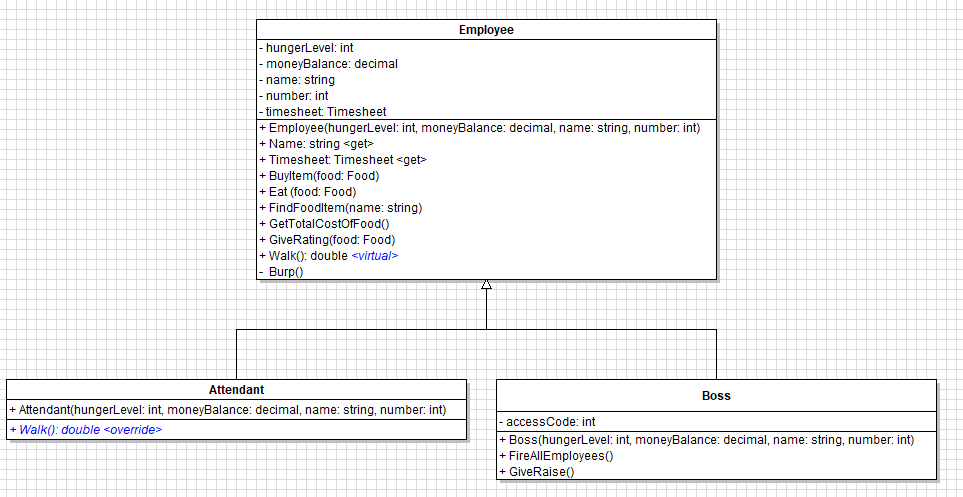

Now we can define an override method in a descendant class that says, "I don't care about what the parent class says I should do, I'm going to do this instead." To implement this we will define an override method in the Attendant class as:

Now when Walk is called on an Attendant object, Visual Studio will first check the descendant class to see if the method exists. If it does, it will use that functionality. If it doesn't, it will go to the parents class to check that one. Let's look at it in action.

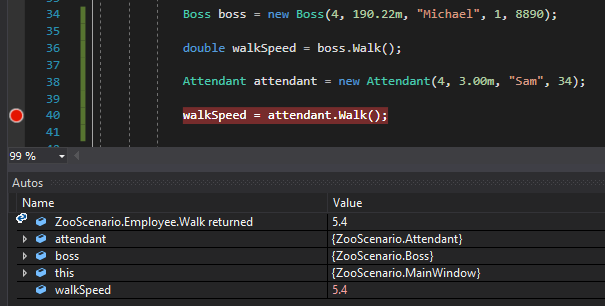

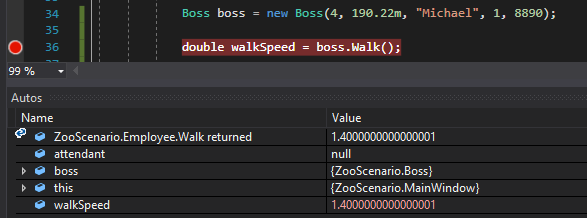

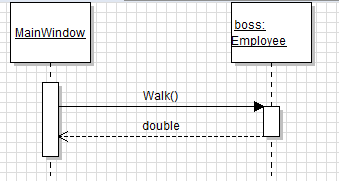

Let's say our Boss object has a Height of 70 and an UrgencyLevel of 2. His speed comes back as being pretty slow since he doesn't have an override and the Employee class's Walk method executes.

So let's call Walk on an Attendant object, instead, with the same exact values. When we do this the speed comes back as the 5.4 we said to return in the Walk method in the Attendant class. If we didn't have that override it would have come back as the 1.4 value the Boss object had.